Tao Te Ching

Early Middle Ages (566 – 1095 CE)

Early Middle Ages, “The Dark Ages,” “The Age of Faith” (566 to 1095)

Petrarch coined this term “Dark Ages” to describe the cultural, intellectual, and economic decline after the fall of the Roman Empire and the characterization became a foundation for the Age of Enlightenment. Defining the long period of Church and belief-rule as a stagnating, backward period and idealizing the previous Greek/Roman era as a far more advanced time animated a new and passionate interest in the old classics, philosophy, and science. Modern historians though have found more positives during this period and use “Dark” only to mean a relative lack of written records. During the the period of Romanticism, this time was redefined as “The Age of Faith” and adulated. More appropriately applied to Northwest Europe where population, trade, and cultural output all declined, “Dark Ages” does not at all apply to Southwest Europe where art and science were flourishing. This era includes the Byzantine Empire, the rise of Islam, the rise of feudalism, the Viking Age, and the founding of the Holy Roman Empire.

Sages (130)

Abbakka Chowta (Rani Abbakka Chowta)

504 – 573 CE

First Indian, woman freedom fighter

“The fearless queen,” Jain sage, warrior, and “first woman freedom fighter of India;” Abhaya Rani was one of the first to resist European colonial attacks. She skillfully fought against the Dutch and British as well as preventing the Portuguese from capturing Ullal several times. Along with fellow Jains, she included Hindus and Muslims in her administration, people from all sects and castes in her armies. Betrayed by an estranged husband, she was finally captured and imprisoned; but, she didn’t give up, broke out, and died fighting. More than 500 years now after her life, she is still revered and celebrated throughout India with stamps, statues, roads, ocean vessels, and festivals named after her.

Abu Yazid al-Bisṭāmī بایزید بسطامی

804 – 874 CE

Famous Sufi, ”King of the Gnostics,” forefather of ecstatic Islamic mysticism; Abu Yazid disavowed excessive asceticism and changed the course of Sufism by shifting the emphasis from discipline, obedience and piety to direct experience and “self-annihilation in the Divine Presence.” An active shrine to him in Bangladesh was built and has been used since 850 CE and he remains an important lineage holder in thelargest Sufi brotherhood, the Naqshbandi.

Aciṅta ཨ་ཙིངྟ་།། ("The Avaricious Hermit")

862 – 912 CE

Mahasiddha #38

Acinta ཨ་ཙིངྟ་། Achingta, “The Greedy Hermit” (second half of 9th century)

Born into extreme poverty, constantly and completely fixated on becoming wealthy; Acinta couldn’t forget his intense desire for riches. Tormented by his greed and unable to escape from it, he met a teacher who gave him a Jambhala wealth practice and initiation into the irresistibleness of a thought-stopping empty mind free from gaining ideas. His dreams of wealth dissolved into a realization of nothing to gain, he became known as “The Thought-Free Guru,” served countless beings, and initiated many disciples into this ultimate reality. Mahasiddha #38

Adi Shankara

788 – 820 CE

Philosopher, theologian, and sage; Shankara unified and established the main philosophical trends in Hinduism. He criticized the dogmatic and ritually oriented schools, emphasized that enlightenment can be realized in this lifetime, and established monastic, personal-practice and direct-experience traditions. Writer of fundamental texts of the Vedanta school and responsible for a major Hindu revival, he is called the source of all the main currents of modern Indian thought. His teachings are similar to Mahayana Buddhism and he was called a "crypto-Buddhist" but he explained the difference being the Buddhism teaching of no self and his that the whole universe is the self - which may be a way of saying the same thing.

Ajogi ཨ་ཛོ་གི་པ། ("The Rejected Wastrel")

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #26

As a child in a rich family, Ajogi was so fat that his parents had to do everything for him. He wouldn’t even get up to go to the bathroom or eat. When this became too much for his parents they first threatened and then actually abandoned him to cremation grounds in the midst of half-burned bodies and wild animals. Still not willing to get off his back, a wandering wise guru challenged his helplessness strategy - not by trying to make him change but by accepting Ajogi’s situation exactly as it was and working with it. This story and practice gives inspiration and a practical path for the most freakish, despised, and rejected. Mahasiddha #26

Al-Ghazali أبو حامد محمد بن محمد الطوسي الغزالي (Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali)

1058 – 1111 CE

Philosopher of Sufism

Legal and theological scholar, rationalist, spiritual philosopher, and Sunni mystic; Al-Ghazali became known as a Mujaddid, a once-in-a-century Muslim "renewer of the faith." Believing that the original Islamic teaching quickly became corrupted, he worked to bring the original wisdom back into awareness and—as a side-effect—brought a critique of the Aristotelian approach that facilitated the advancement of European science. He helped integrate Sufism into mainstream Islam and his teaching became a profound influence and foundation for Islamic business ethics and practice.

Al-Kindi (Abu Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ)

801 – 873 CE

While European countries were still stuck in the dark ages of almost universal superstition and ignorance, Al-Kindi - knows as “father of Arabic philosophy” - precipitated the “Moslem Enlightenment,” one of the true golden ages of human history, a time that threw off its dogmatic shackles of uncritical belief and advanced science, direct experience unfettered by external sources, understanding of the sense and not just the words. A famous historian, physician, polymath, musician and mathematician; he brought Hellenistic wisdom into the Muslim world and shocked his contemporaries by appreciating Christianity.

Alan Gua (Алун гуа)

832 – 884 CE

"Alun the Beautiful"

Living ten generations before Genghis Khan, Alan Gua is credited with forging the original Mongol clans together when she taught her five sons the parable of the five arrows showing them how easy it is to break one arrow but how impossible when the five are bound together. This image was powerful enough to overcome her first two son’s suspicions and jealousy when she had three more sons after their father died and explained the new births as a result of a heavenly, “glittering visitor” who came through her yurt’s roof on moonbeams “like a yellow dog.” This story/image transmitted from the Mongols to the Iroquois Confederacy through Deganawida and Hiawatha and to the US Founding Fathers becoming incorporated as the Great Seal of the United States and the same essential message into the US Constitution.

Alhazen بوعلی محمد بن حسن بن هیثم (Ibn al-Haytham)

965 – 1044 CE

One of the most famous and influential Iraqis, philosopher, engineer, astronomer, animal psychologist and one of the first theoretical physicists,; Alhazen understood, used, and promoted the scientific method 200 years before Renaissance scientists. Well-known and honored as "The Physicist" in medieval Europe and writing more than 200 books, he made huge contributions in the fields of optics, astronomy, mathematics, visual perception, and the scientific method. His work on a magnifying lens laid the foundation and inspiration for Roger Bacon and friends’ creation of microscopes and the telescope. He was the first to describe how vision occurs as well as the camera obscura effect on which all photography depends. Apostle of critical thinking and skepticism, he advocated becoming “an enemy of all we read, attacking it from every side.”

Arwa al-Sulayhi (Al-Malika al-Ḥurra)

1048 – 1138 CE

The stellar example in Muslim history of an independent queen; Arwa ruled Yemen, was the greatest leader during the Sulayhid Dynasty, and was - for the first time in the entire history of Islam - a woman given the title of hujja, the highest status in Islam. Extremely beautiful, intelligent, scholarly, brave, and powerful; she studied science, poetry, history, completed practical and beneficial infrastructure projects, supported agriculture, and built many schools. Her direct lineage continues today in both Yemen and India.

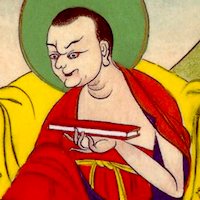

Atisha ཨ་ཏི་ཤ་མར་མེ་མཛད་དཔལ་ཡེ་ཤེས་ (Atiśa Dīpaṃkara Śrījñāna)

980 – 1054 CE

One of the major figures in classical Buddhism, Atiśa inspired students and teachers from Tibet to Sumatra. Born into royalty in the capital of the Pala Empire, Atiśa became a monk and scholar said to have studied with more than 150 different teachers. Founder of the Kadam School, he traveled and taught widely. In The Seven Points of Mind Training he condensed Buddhist teachings into easy-to-remember slogans. The lineage of people using this technique includes Aesop, Balthasar Gracian, Ben Franklin, Erasmus, Yang Xiung as well as The Dhammapada.

Avicenna أبو علي الحسين بن عبد الله بن الحسن بن علي بن سينا (Ibn-Sīnā)

980 – 1037 CE

Persian polymath, spur to the Islamic Golden Age, poet, doctor, scientist, philosopher and one of the most significant thinkers and writers of his time; Avicenna wrote over 450 books one of which became the standard medical text for European universities up until as late as 1650. With influence from Plato and Aristotle, he clarified the distinction between the words and the sense, taught a spiritual path beyond motivations of hope and fear, reconciled the conflict between reason and faith, and his works according to Will Durant, “mark the apex of medieval thought and constitute one of the major syntheses in the history of the mind.”

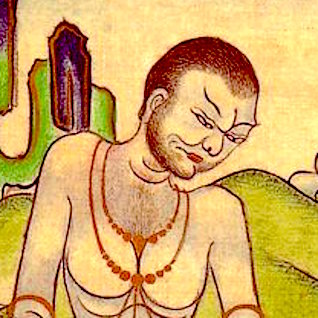

Bhadrapa

8th century CE

A “goody-two-shoes,” Brahmin purist intent on complete political correctness and purity; when the cleanliness obsessed and wealthy Bhadrapa met a homeless yogin he was repelled and cried out, “Unclean!” The teacher countered that physical form isn’t unclean, only the psychological corruption of body, speech, and mind. Bhadrapa realized his bigotry, that real purity means giving up ego-clinging and has nothing to do with following conventions and religious rules. He became a disciple, renounced his caste privileges and practices, cleaned latrines as his spiritual practice and became a great Mahasiddha himself.

Bhadrapa

8th C. CE

A “goody-two-shoes,” Brahmin purist intent on complete political correctness and purity; when the cleanliness obsessed and wealthy Bhadrapa met a homeless yogin he was repelled and cried out, “Unclean!” The teacher countered that physical form isn’t unclean, only the psychological corruption of body, speech, and mind. Bhadrapa realized his bigotry, that real purity means giving up ego-clinging and has nothing to do with following conventions and religious rules. He became a disciple, renounced his caste privileges and practices, cleaned latrines as his spiritual practice and became a great Mahasiddha himself.

Bhikṣanapa བྷི་ཀྵ་ན་པ། ("Siddha Two-Teeth")

940 CE –

Mahasiddha #61

Bhikshanapa བྷི་ཀྵ་ན་པ། “Siddha Two-Teeth” (10th century CE)

Low caste and very poor, Bhikshanapa unexpectedly inherited some wealth. Like most people today winning a lottery or inheriting unaccustomed riches, he quickly lost it all along with his fair-weather friends. This led to a period of intense self-loathing and depression but also an openness to meeting and hearing a teacher and new way of experiencing the world. Seeing through his consumerism andspiritual materialism, he metaphorically (and possibly physically too), lost all but two of his teeth which became symbols for the balance and harmony of wisdom and skillful means. Resuming his external life style of roaming from village to village, he transformed from a miserable, needy beggar only thinking about himself into a wonderful teacher constantly dedicated to helping others. Mahasiddha #61

Campaka ཙ་མྤ་ཀ (“The Flower King”)

820 CE –

Mahasiddha #60

Extremely wealthy, powerful, caught up in pleasure, and sitting on a throne made from sweet-smelling flowers; Kampala met a wandering yogi. He tried to impress the sage with the splendors of his kingdom and the beauty of his flowers but the sage told him the truth, that his flowers smelled great but his body not so much, that his realm was wonderful but before long it and he would be gone. Realizing the superficiality and meaninglessness of his life, Kampala began a spiritual path but only shifted his physical materialism into spiritual materialism. Directed to focus his meditation on “the flower of pure reality,” he practiced and finally realized the empty essence of his mind. Mahasiddha #60

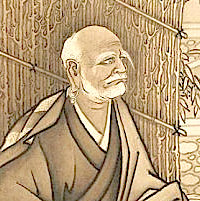

Cao Daochong 道寵 (Daochong or Ts’ao Tao-Ch’ung)

fl. 960 - 1268

Mysterious Taoist nun during the Tang Dynasty, Cao Daochong walked in Lao Tzu’s footsteps of inscrutability and disregard for fame and fortune. Though unassuming and humble, her deep insight, wisdom, and compassion speak through the centuries through her book, the Lao-tzu-chu. Living during the time of the great Mahasiddhas in India, Naropa and a major transmission of Buddhism into Tibet, she was a contemporary of other great women teachers like Dharima, Manibhadra, Niguma, Arwa al-Sulayhi, Heloise, and Hildegard of Bingen.

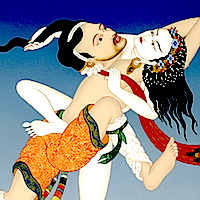

Carbaripa ཙ་རྦ་རི་པ། (Carpati, “The Petrifier”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #64

Legends about Carbaripa seem to fit better in the shaman lineage than the buddhist one. These stories could be an example of reinterpretating symbols from a different point of view. From the shamanistic point of view, stories about him turning people to stone imply magic and the power of place. From the buddhist viewpoint, these can be interpreted as a teacher’s ability to disperse disciples discursive thoughts and distractibility, their skill in inspiring the transformative powers of deep meditation. A deeper meaning can be understood in how he liberated people from their petrified social and cultural concepts. The main legend about him describes him helping a young wife abused and beaten by her wealthy husband and his aggressive, controlling mother. The stories don’t describe but pictures of him frequently show him copulating in the sky with this young wife. Mahasiddha #64

Catrapa ཙ་ཏྲ་པ། ("The Lucky Beggar")

750 – 850 CE

Mahasiddha #23

Catrapa while begging always carried a small dictionary that attracted a wise teacher who asked him about the book and then his life. This led to teachings and a practice of dissolving all concepts, prejudice, negative and moral conditioning, and a blending of action with perception into a deep, non-dual awareness of each everyday experience in life. Instead of teaching morals, ethics, and discipline; he exemplified and taught the crazy wisdom of wu wei, enlightened spontaneity based on direct, unfiltered realization. Mahasiddha #2

Cauraṅgipa ཙཽ་རངྒི་པ། ("The Dismembered Stepson")

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #10

Saintly son of a king, Cauraṅgipa’s arms and legs were cut off when he refused the amorous advances of his step-mother who lied and slandered him. The servants offered to take the body parts from their own children but he refused, not wanting to cause harm to others. Left to die under a tree, he met his guru Minapa who gave him meditation practices that saved his life and led to his complete realization, “the one taste of all things.” His physical loss of limbs became a foundation and benefit to his practice. (graphic credit: Robert Beer) #10

Chamaripa ཙཱ་མཱ་རི་པ། (Cāmāripa, “The Siddha Cobbler”)

840 – 940 CE

Mahasiddha #14

A poor cobbler in ancient India, Chamaripa worked long hours making and repairing shoes while he dreamed of a higher, more meaningful life. Disgusted with the emptiness of his life he begged teaching from a wandering teacher and began a practice of visualizing his work as meditation practice, his tools and materials as symbols for deep understandings. He discovered how the thread that tied his shoes together was like the thread of emptiness (shunyata) that connects a core enlightenment back through our graspings for fame, fortune, pleasure, and power. Mahasiddha #14

Chéng Xuanying 成玄英 (Ch'eng Hsuan-ying)

631 – 655 CE

A Daoist monk and exceptional scholar during the early Tang dynasty, Xuanying wrote highly respected commentaries and summaries on both Lao Tzu and Chang Tzu. The first emperor of Tang invited him to the capital and gave him the title, “Master of West China” but he was later exiled. He taught that “mystery” means profundity, that it persists neither in Being nor in Nonbeing, that we should not persist in “mystery,” but negate it. This led to Zhuangzi's thought and the Buddhist philosophy of the Middle Way. His tradition was called the “Twofold Mystery School” and his writings on this made it the main influence on Daoist philosophy of the time.

Cheng Zhu 程俱 (Ch‘eng, Chü, Zheng, Ru, Ju Cheng)

1078 – 1144 CE

Neo-Confucian founding uncle

Political critic and scholar-official, Cheng Zhu became a major critic of the political policies of his era and an important influence on the development of neo-Confucianism. A philosophical school named after him became a strong influence advocating morality as the foundation for political leadership.

Dārikapa དཱ་རི་ཀ་པ། (“Slave-King of the Temple Whore”)

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #77

In a somewhat typical story, this wealthy and powerful king enjoying all the pleasures of his privilege meets an enlightened master, realizes the emptiness of his life, and gives away everything to follow his guru. In this case though, he also gives away his body and freedom which his teacher sells to a famous prostitute, Darima. After many years of serving as her slave and practicing his dharma; Darima, her many attendants, guards, slaves, and customers became disciples who he taught and served for many years. Mahasiddha #77

Dazu Huike (Dz Huk)

487 – 593 CE

Student of and lineage holder after Bodhidharma, 29th Zen Patriarch, 2nd Chinese Patriarch of Chan, insightful scholar of both Taoism, Buddhism, and ancient Chinese texts; Huike received the title Dazu (“Great Ancestor”) from the Tang emperor De Zong. To choose a successor when Bodhidharma planned to return to India, he asked his disciples to express their realization. Each gave poetic answers but Huike only stood silently invoking Bodhidharma’s observation, “You have attained my marrow.” Hike’s teachings diverted from the Indian tradition of a gradual path and emphasized sudden enlightenment, realization through meditation rather than study, and practice free from any gaining ideas or dualism.

Ḍeṅgipa ཌེངྒི་པ། (“The Courtesan's Brahmin Slave”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #31

Brahmin minister to a king who left his wealth and status for a spiritual path, Ḍeṅgipa met his guru but because he had no appropriate gift to give offered his body as a slave. His guru then - to reduce his royal pride, racial discrimination, and to give him a practice - sold him as a slave to a prostitute. After 12 years of service mainly threshing rice, he discovered the one taste of all things, merged space and awareness, and became spiritual teacher to the prostitute as well as to the hundreds of people in that district. Mahasiddha #31

Dharima

10th century CE

Prostitute, consort of the famous Mahasiddha Tilopa, slave owner and student of Mahasiddha Luipa (probably a different person with same name and profession); Dharima and Tilopa started on this spiritual path together, practiced together for many years, and when enlightened taught together. They learned the "Illusory-body" yoga from Nagarjuna’s tradition, Dream yoga from Caryapa, Cakrasamvara and the Clear Light from Lavapa, and from the woman saint Subhagini, Candalini-yoga and the Hevajra tantra. They forged these 4 traditions into what became the Kagyu lineage of Mahamudra that continues powerfully today through teachers like Chogyam Trungpa and the Karmapas.

Dharmapa thos pa’i shes rab bya ba

915

“The Perpetual Student” — Mahasiddha #36

Dharmapa lived his life as a scholar, a professor, a pandita. He spent his entire life studying and teaching but gave little time or attention to meditation or other practices. He didn't become aware of the gap this left in his awareness until he was old and blind. He realized his need for a teacher but was no longer in a position to fine one. A dakini appeared in a dream however, and taught him the difference between analytical understanding and realization. He showed Dharmapa how he could—like a blacksmith melting pieces of iron into a single ingot—melt all the disparate strands of his knowledge into a unified experience of true mind and wisdom.

Dhilipa དྷི་ལི་པ། (“The Epicurean Merchant”)

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #62

Dhilipa had a sesame oil pressing business that did really well and made huge profits. He devoted this wealth to personal pleasure-seeking and is said to have had at each meal 84 main courses, 12 deserts, and 5 kinds of beverages prepared by the best chefs of the time. After one of these sumptuous banquets, a dharma teacher guest questioned him about how far his pleasure seeking was really taking him and pointed out that he could go on making more and more money but it wouldn’t bring him any more true happiness or realization. Like he extracted oil from sesame seeds, Dhilipa then extracted dualistic concepts from experience, realized the union of opposites, and burned the pure flame of awareness. Mahasiddha #62

Dhobīpa དྷོ་བཱི་པ། (“The Wise Washerman” )

806 – 906 CE

Mahasiddha #28

From a family of washermen in a country where purification and cleanliness were high spiritual values and people were expected to take ritual baths twice a day, Dhobipa spent his time washing clothes and cleaning things. A wandering, wise yogi visited him with a piece of coal and asked him to clean it, to take out the stain. Recognizing that the impossibility of cleaning coal by washing is like the impossibility of realizing wisdom with dogmatic belief, increasing goodness with materialistic intentions, or healing inner wounds with mindless ritual; Dhobipa went beyond convention and became a great teacher himself. Mahasiddha #28

Dombipa

10th C. CE

Enlightened ruler of Magadha (Kashmir), Dombipa treated all his subjects like a “father would treat his only child” but his country suffered almost endless war, crime, famine, and poverty. He brought back prosperity, peace, and health but when he took a low caste “untouchable” as consort and started drinking large amounts of alcohol, the shocked people forced his abdication. After 12 years when the country’s problems returned, they begged him to return which he did “riding on a pregnant tiger” with his consort. To rule them again, he asked that they abandon the caste system. When they refused he went back into his meditation saying, “My only kingdom is the kingdom of truth.” This lineage continues with the Trungpa Tulkus.

Dongshan Liangjie 洞山良价 (Dòngshān Liángjiè; Tōzan Ryōkai)

807 – 869 CE

Famous poet, Shaolin Monastery Chan monk, founder of the Caodon school which became the Sōtō Zen lineage when taken to Japan in the 13th century by Dōgen; Dongshan helped develop the koan tradition. Drawing from the I Ching, inspired by the Sandokai, and inspiring the Oxherding Pictures, his famous poem Five Ranks described the path and unification of absolute and relative realities, the highest spiritual realization in the middle of everyday life.

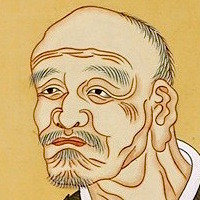

Du Fu 杜甫 杜甫

712 – 770 CE

Though Li Bai in the West is most often considered China's greatest poet, in the East, that honor most often falls to Du Fu, "the Chinese Shakespeare." Historian, sage, and compared to Milton, Burns, and Wordsworth; Du Fu failed the Chinese examinations for public office although the subject was poetry but became one of China's most influential writers. A close friend and traveling companion of Li Bai during a time of intense political change, his fortunes rose and fell from the highest honors to the depths of misery finally to be robbed of the straw in his bed while he was too weak to resist. In Japan considered the "Saint of Poetry" and the major influence on the greatest haiku poet, Matsuo Bashō; Du Fu excelled at reconciling opposites, considered "everything in this world is poetry," and became one of the greatest writers in any language.

Dukhandhi དུ་ཁངྡྷི་པ། ("The Scavenger")

798 – 898 CE

Mahasiddha #25

A low caste sweeper surviving by scavengering thrown-away pieces of cloth and making them into clothes, Dukhandhi - whose name means “he who unites duality” - thought he was prevented from good meditation practice by his need to survive by constantly sewing. His teacher pointed out how he could actualize the meaning of his name by uniting his necessary life experience with his spiritual path, that they are no different. After many years of stitching together spiritual practice with his daily life experience, he became enlightened and a great teacher. Mahasiddha #25

Empress Suiko 推古天皇 (Suiko-tennō)

554 – 628 CE

Emperor’s daughter, Buddhist nun, first and only confirmed Japanese Empress Regnant of Japan; Suiko’s many achievements include adopting a more useful calendar cycle, the 17-article constitution (written by Shotoku), and the official recognition of Buddhism by the issuance of the Flourishing Three Treasures Edict in 594. She was one of the first Buddhist monarchs in Japan, sponsored Buddhist temples and monasteries, and firmly established Buddhism in Japan. She orchestrated China’s first diplomatic recognition of Japan and close cultural contact with both China and Korea.

Ferdowsi فردوسی (Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi)

940 – 1020 CE

"undisputed giant of Persian literature"

Philosopher, poet, and one of the world's most influential literary figures; Ferdowsi wrote what became Iran's national epic as well as history's longest poem written by a single poet. Considered the "father of the modern Persian language," he influenced all the writers who followed him, regenerated the Persian language, and revived many cultural traditions.

Gampopa སྒམ་པོ་པ། (Sönam Rinchen, Dakpo Rinpoche)

1079 – 1153 CE

Doctor, student of Milereapa, and founder of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism; Gampopa started as a householder with a family and then became a monk when they died. In a similar way, he changed the yogi/householder style of Marpa and Milarepa into a monastic approach. He integrated Atisha’s Kadam school with the Mahamudra teachings of Milerapa and four of his disciples founded the four main Kagyu schools. Though on the surface, this moved the tradition away from the non-thought, wisdom-beyond-words approach and instead emphasized rules and concepts; stories tell of Taoist teachers and influences on Gampopa, secret practices and teachings he gave in this lineage as well.

Gesar of Ling གེ་སར་རྒྱལ་པོ།

11th century CE

Generally considered a real person in Tibet and Mongolia, a legend like King Arthur by western scholars, Gesar represents the heroism and wisdom necessary to overcoming the negative impulses in society, culture, and government that oppress people and prevents happiness from flourishing. Called the world's last living epic, the Gesar story includes more than 120 volumes, a million verses, and 2100 hours of oral performance - the largest body of epic literature in history. The Gesar epics derives from Indian Buddhism, native Tibetan Bön, and alchemical Taoism. Like Homer’s Iliad, they include performance, poetry, philosophy, education, politics and religion.

Ghaṇṭāpa གྷ་ཎྚཱ་པ། (“The Celibate Bell-Ringer”)

early 9th century

Mahasiddha #52

One of the earliest Kalacakra practitioners, founder of the Pancakrama Samvara lineage, Nalanda scholar, and guru to a king; Ghantapa became a symbol for appropriate action outside the confines of rigid ethics and morality, allegiance to personal insight over status quo strictures, and belief in the sense above the words. As a celibate monk, he saw through the chains of public and monastic opinion, desire for fame and acceptance, dissolved his vows, drank liquor, had sex, took on a consort, and had a child. His example inspired the people of his village and hearers of his stories during the centuries to dissolve their self-righteousness, prejudice, and sectarianism. Mahasiddha #52

Godhuripa གོ་དྷུ་རི་པ། (“The Bird-Catcher”)

700 – 800 CE

Mahasiddha #55

Godhuripa’s livelihood was based on killing birds. He knew this was not good and created bad karma for himself; but, he didn’t think he had a choice because this was all he knew how to do. A teacher challenged this opinion pointing out that selling his soul for material gain only made things worse in the long run. He gave Godhuripa a spiritual practice of listening to the birdsong not to find and kill the birds but to discover “the sound of silence,” the one taste and unity of sound and emptiness. He let all the birds go, gained direct perception of sound, and became a teacher with hundreds of students. Mahasiddha #55

Goraksa ཤྲཱི་གོ་རཀྵ་ནཱཐ྄། (Nāth Siddha Gorakṣa, "The Immortal Cowherd")

10th Century CE

First haha yoga teacher, founder of India’s largest yoga sect, and non-sectarian Tantric leader; Goraksa assimilated Buddhist insight and understanding into a Hindu context free of duality and integrated tantric practices into Buddhist philosophy. His life symbolizes and his teachings reinforce that every condition and situation people find themselves in has equal potential for realizing the highest awareness. He emphasized the potential in even the most negative circumstances and taught to appreciate everything rather than fighting against our experience and trying to attain a fantasy of what we might think is better.

Han Shan (Cold Mountain)

c. 730-850 CE

Claimed by Buddhists as a Buddhist, by Taoists as a Taoist; Han Shan poked fun at both and living beyond any narrow categories like these, through his poems communicated a universal wisdom and truth. Not attached or attracted to honor and gain, he laughed at offered high positions and wealth. The favorite poet of everyone from Wang Anshi (1021-1086), one of China’s most famous prime ministers to Jack Kerouac who in 1958 dedicated his book Dharma Bums to him, Han Shan’s poems express complete spontaneity, total indifference to praise and blame, and continual realization of pure consciousness in the simple, ordinary details of life.

Heloise

1090 – 1164 CE

An orphan raised in a convent, Héloïse became a brilliant scholar, one of the earliest and most radical feminists, a powerful abbess over multiple convents, and half of one of the most famous and talked about relationships of her era. As femme fatale to Peter Abélard when he was on the rise toward becoming a pope, her influence caused him immense humiliation and pain as well as the inspiration for some of the most important books of the time, a regard for the sense over the words, and a declaration of philosophical independence for reason over belief. It’s become a tradition for the hoping-to-find-true love to leave letters at their crypt.

Hilda of Whitby

614 – 680 CE

Living in a brutal time of violent warlords and kings, Hilda’s mother was a poor, homeless widow. From this humble and challenging beginning, she became a powerful advisor to officials, bishops, and kings. The historian Bede wrote, “All who knew her called her mother because of her outstanding devotion and grace.” Abbess and founder of several monasteries, five men who lived and studied at one of these became bishops and two of them are now revered as saints. She is considered a patron saint of poetry, learning and culture.

Hóngzhì Zhēngjué 宏智正覺 (Shōgaku)

1091 – 1157 CE

A highly prolific literary giant, Hongzhi taught “silent illumination,” shikan taza (just sitting), a return to our original nature without gaining ideas, letting go of conditioning in completely relaxed awareness, and a return to the world. These teaching became a root influence on the beginnings of the Soto Zen school. He was abbot of the Tiantong Monastery where later Eihei Dogen studied. Dogan brought these teachings to Japan extensively quoting Hongzhi describing him as an “Ancient Buddha.”

Huangbo Xiyun 黄檗希运 (Huangbo Xiyun, Huángbò Xīyùn, Obaku)

? - 850 CE

An uncompromising and fierce teacher, Huángbò often hit and shouted at his students including a future emperor of China. Though according to the Blue Cliff Record he was seven feet tall, very little is known about his personal life — unsurprising given his uncompromising disregard for conceptual thinking, his focus on egolessness and One Mind. Once when he told his students that in all of China there are no teachers of Zen, a student asked him how he could say that since he was teaching them. Huángbò answered, “I didn’t say there was no Zen, just no teachers.”

Huating Decheng 華亭德誠

820 – 858 CE

After intense study with Chan Master Yaoshan Weiyan, Decheng moved to Hua Ting and lived on a small boat. He semi-anonymously stayed in the background and passed as a very ordinary person. As an occupation, he took people across a river while—with discrete subtlety—teaching them his Chan Buddhist understanding. In a famous story, he triggered a student's enlightenment by pushing him off the boat into the river. After the students realization, Dechenbg told him not to think about him anymore and fell off the boat into the water liberating the student from the golden chains of hero-worshipping delusion.

Hui Hai 大珠慧海

788 – 831 CE

Hui Hai 大珠慧海 Baizhang Huaihai (788 - 831)

Tang dynasty Chinese Chan monk, and author of the still-influential book, Essential Gate for Entry Into Sudden Enlightenment; Hui Hai became known as the “Great Pearl” because his teacher Ma-tsu Tao-i was so impressed when he read this book he praised it as “a great pearl, perfect and bright illumination that penetrates everywhere without impediment. Teacher to the famous Huangbo Xiyun, he established a set of rules for Chan monasteries still used today as well as architectural and lifestyle forms. Some of these included farming and self-sufficiency skills that enabled the Zen monasteries to survive during times of persecution and the influential saying, "A day without work is a day without food" (一日不做一日不食 "One day not work, one day not eat"). Ta-chu Hui-hai

Huineng 惠能 (Huìnéng, Enō)

638 – 713 CE

The Sutra of Hui Neng

Traditionally seen as the Sixth and Last Patriarch of Chán Buddhism, Huineng symbolizes the essence of Zen and the non-thought lineage. From a poor family, Huineng’s father died when he was young and he never learned to read and write. While working as a laborer, he heard the Diamond Sutra and immediately set off to study with the Fifth Patriarch. Since illiterate, he could only work at the monastery doing chores like chopping wood and pounding rice. Because of his deep understanding and realization though, he because the dharma heir. Like the famous story about not mistaking a pointing finger for the moon, he deeply understood the sense, not only the words.

Huizong 徽宗 (Emperor Huizong of Song)

1082 – 1135 CE

Great artist, failed ruler

Polymath, poet, musician, called “one of the greatest Chinese artists of all time,” but an incompetent leader taking disastrous advice to disastrous results; Huizong demonstrated the difficulty of blending art and politics. Collecting over 6000 paintings, he sponsored artists, wrote poems, painted, reformed court music, and wrote dissertations on Taoism, tea ceremony, and medicine. His foreign policy decisions however and military neglect led to a Jurchen invasion and the ending of the Song Dynasty, his demotion to commoner status, and the last 8 years of his life spent as the “Besotted Duke" jailed in a remote, cold province prison. He promoted monumental philanthropic efforts including founding orphanages, hospitals, and schools; but, his failure to balance his religious Taoism with the Confucian mainstream prevented the maintenance of a strong government.

Indrabhūti ཨིནྡྲ་བྷཱུ་ཏི། ("The Enlightened Siddha-King")

892 CE –

Mahasiddha #42

Indrabhuti ཨིནྡྲ་བྷཱུ་ཏི། The Enlightened Siddha-King (late 9th century)

“The first tantrika,” archetypal tantric king, and inspiration for several tantric lineages; Indrabhuti for political reasons pledged his Buddhist sister Laksminkara in marriage to the prince of a neighboring Hindu kingdom. She went to live with the neighboring prince but soon became disillusioned with the materialism, superstition, and decadence of her new country. Late one night she fled the palace and found a cave in the mountains where she lived and practiced meditation, attained enlightenment and scandalously started teaching untouchables. This greatly upset the Hindu king but inspired Indrabhuti to do the same and leave the comfort of palace life to devote himself completely to his spiritual path. He rejected however a path that rejected sensual pleasure and sex and practiced the Guhyasamaja father-tantra in the Anuyoga Dzogchen lineage. Mahasiddha #42

Jālandhara ཛཱ་ལནྡྷ་ར་པ། ("The Ḍākinī's Chosen One")

888 CE –

Mahasiddha #46

Jalandhara ཛཱ་ལནྡྷ་ར་པ། “The Ḍākinī's Chosen One” (late 9th century)

Another wealthy and privileged brahmin who saw through the materialistic values of his culture and renounced it to search for a more meaningful life, Jalandhara left everything to live in a cremation ground meditating. Going on to become an important mother-tantra siddha, one of the nine naths, and guru to 10 of the 84 Mahasiddhas; he founded one of the two main nath lineages (A Hindu tradition favored by Kabir that blended Shaivism, Buddhism and Yoga traditions using Hatha Yoga to transform the physical into awakened perception of “absolute reality”), taught practices that unify the male and female forces, dissolve the subject/object dichotomy, and open the non-dual doors of perception. Mahasiddha #46

Jayānanda ཛ་ཡཱ་ནནྡ།། ("Crow Master")

11th - 12th century

Mahasiddha #58

A Tantric Buddhist master practicing in Bengal during a time when Buddhism was illegal, Jayananda was exposed by a jealous neighbor and imprisoned by the anti-Buddhist king. Before being captured though, he had befriended and fed a big flock of crows. In Tibetan culture crows are considered bad omens, capable of bringing great harm, and feared. But in a symbol of tantric transformation, Jayananda had made the crows allies. Then—metaphorically as crows or symbolically as an inclusion of the negative—the king was upended, reduced to hiding under his thrown, and as a consequence became a great and influential siddha himself. Mahasiddha #58

Jianzhi Sengcan 鑑智僧璨 (Jiànzhì Sēngcàn)

529 – 606 CE

The Third Chinese Patriarch after Bodhidharma and thirtieth Patriarch after the Buddha, Sengcan wrote famous Chinese poems called Xinxin Ming. Because of a Buddhist persecution of the time, he went into hiding in the mountains and later wandered without a home for 10 years. He taught the elimination of all duality, going beyond words to the sense, and the contemplation of wisdom. Hsin Hsin Ming

Joshu, Zhàozhōu Cōngshěn 趙州從諗

778 – 897 CE

Joshu, Zhàozhōu Cōngshěn 趙州從諗 (778–897)

Called the greatest Chan master of the Tang dynasty,” Joshu traveled extensively his entire life not slowing down or teaching until he was 80 years old and then for 40 more years. Famous for his incomprehensible behavior and paradoxical teachings, many famous koans come from his realization including many in the Blue Cliff Record and one of the most well known ones that begins The Gateless Gate. His main temple was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution but later rebuilt and now a large center for modern Chinese Buddhism.

Kambala ཀམྦ་ལ་པ། ("The Black-Blanket-Clad Yogin")

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #30

Closely connected with the feminine archetype of emptiness without ego and original authority on the mantrayana tantras, Kambala began his spiritual path as a king, left it and became a monk. He then left the relative luxury of the monastery to become a wandering yogi. Challenged by his teacher to leave even the comforts of that life, he left behind everything but a black blanket that was also taken away from him and eaten by evil feminine forces. After his turning them away from their evil ways, they gave the blanket back in small pieces that he sewed back together becoming known as “The Black-Blanket-Clad Yogin. Mahasiddha #30

Kanakhala ཀ་ན་ཁ་ལཱ། ("The Younger Severed-Headed Sister”)

late 9th century

Mahasiddha #67

One of two unmarried, mischievous daughters; Kanakhala’s father married her off to an unsuspecting boy from another village. He soon realized though and an intense and constant “battle of the sexes” began. As their lives sunk into more and more misery, she suggested running away to another country. Mekhala, however, realized that their problems were self-created and would follow them wherever they travelled. This realization somehow seems to have triggered an encounter with a famous guru who initiated them onto a spiritual path. After 12 years, they returned to the guru but brought no offerings. According to the story, the guru asked for their heads and they immediately cut them off with “the keen-edged sword of pure awareness.”

Kanhapa ནག་པོ་པ། ("The Dark-Skinned One")

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #17

A founder of the Nath lineages, guru to many famous gurus, great poet and singer but proud, easy-to-anger, aggressive and arrogant; Kanhapa’s story doesn’t easily fit into a list of enlightened teachers. He successively achieved levels of realization but didn’t listen to his spiritual guides, disobeyed his guru, got proud, and then suffered a downfalls. This continued until he aggressively stole some fruit, got into a fight with the dakini who owned it, and then was killed by her in retaliation. In the Crazy Wisdom, Sacred Clown, Trickster tradition; Kanhapa shows by bad example how not to behave, demonstrates deflating the ego of spiritual materialism, and shocks students out of their complacency.

Kaṅkaṇa ཀངྐ་ཎ་པ། (“The Siddha-King”)

11th century CE

Mahasiddha #29

A prosperous king addicted to indulging his every whim and desire, Kangkana met a wandering wise man who pointed out how empty his life was - like a mouse on a treadmill chasing imaginary pleasures. Kangkana realized the truth of this but not wanting to abandon his position and kingdom to become an ascetic asked for a practice he could do while remaining a king. This practice taught him the oneness of experience and he transcended the differences between pleasure and pain, loss and gain, stress and strain. Mahasiddha #29

Kaṅkāripa ཀངྐཱ་རི་པ། (”The Lovelorn Widower”)

8th C. CE

Mahasiddha #7

A low caste householder happily married and filled with sensual pleasure, Kankaripa collapsed into despair when his beloved wife unexpectedly died. Confronted and asked by a wise teacher why he was letting himself grieve so much and wouldn’t let go of the corpse when “All life ends in death, every meeting ends in a parting;” he learned meditation practice, how to visualize his dead wife as a Dakini, attained ultimate realization, and became a wise, enlightened sage. Understanding how big as well as small “disasters” can become the most important, beneficial, life-changing events in our lives; this ordinary, uneducated man exemplifies transforming another affliction into spiritual path.

Kantalipa ཀནྟ་ལི་པ། ("The Ragman-Tailor")

800 – 900 CE

Mahasiddha #69

Living life on the deep, dark bottom of society as an untouchable and barely surviving with never a full stomach by digging rags out of garbage and sewing the small pieces into cloth; Kantalipa represents how to deal with misery, poverty, and society’s revulsion—not an easy challenge. When he accidentally stabbed himself with a needle and the blood ruined a piece of cloth he had been working on for a long time, Kantalipa hit bottom rolling around on the ground, tearing his hair, and moaning like an animal. “When the student is ready, the teacher arrives” and Kantalipa was ready. He began an intense meditation practice experiencing his needle as mindfulness, the tread as compassion, and the rags as empty space. Mahasiddha #69

Kapālapa ཀ་པཱ་ལ་པ། (“The Skull Bearer”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #72

Suicidal and lost in despair after his wife and 5 children died from a plague, Kapalapa met in a cremation grounds Kanhapa who suggested he practice the dharma rather than just die. Making a bowl from his wife’s skull and ornaments from his children’s bones, Kanhapa taught him to see the emptiness of the bones as a creative, fulfillment meditation. After years of practicing in this way, Kapalapa became a great teacher himself helping hundreds of disciples. Mahasiddha #72

Khaḍgapa ཁཌྒ་པ། ("The Fearless Thief")

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #15

Hiding in a cremation ground after a failed robbery, Khadgapa met Carpati, an enlightened yogi and asked for some meditation practices that would make him into an invincible, uncatchable thief. Carpati gave him practices and instructions for finding the “radiant sword of undying awareness.” Khadgapa thought this sword would cut his physical enemies but instead it cut through his real foes: anger, hatred, aversion, desire, greed, sloth and stupidity. In spite of his life of crime, Khadgapa became a great Mahasiddha himself proving that any lifestyle and profession can launch the highest realizations. #15

Kirapālapa ཀི་ར་པཱ་ལ་པ། (Kirapalapa, "The Repentant Conqueror")

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #73

A retelling of Ashoka’s story set in more recent times, Kilapa was a rich, powerful, and insatiable king obsessed with continually getting more wealth, power, and territory. When he personally confronts the horrors of war he completely changes and dedicates his life and kingdom to helping others, peace, education and poverty alleviation. His spiritual practice is distracted by the affairs of state until his guru gives him a visualization practice seeing his subjects as sacred beings and his kingdom as “the infinite emptiness of mind.” He then becomes a great siddha himself.

Koṭālipa ཀོ་ཊཱ་ལི་པ། ("The Peasant Guru")

1084 CE –

Mahasiddha #44

Kotalipa ཀོ་ཊཱ་ལི་པ། “The Peasant Guru” (2nd half of eleventh century)

Kukkuripa ཀུ་ཀྐུ་རི་པ། ("The Dog Lover")

915 CE –

Mahasiddha #34

Kukkuripa “The Dog King” ཀུ་ཀྐུ་རི་པ། (10th century CE)

A wandering ascetic, Kukkuripa found and adopted a starving dog brought it back with him to the cave where he lived and meditated. Kukkuripa’s meditation practice took him to pleasurable, psychological god realms but memories of his dog connected him back to the real world where he saw his loyal dog sad, thin, and starving. Spurning the luxury, comfort and extravagance; he returned to the cold, dark, very uncomfortable cave out of compassion for the dog. The dog then became his teacher blending his mind-stream with the deepest insight of all the Buddhas. Naropa sent Marpa to study with him and he became one of Marpa’s most important teachers, famous for his songs of realization, and a “patron saint” for all the downtrodden and oppressed. Mahasiddha #34

Kumbharipa ཀུམྦྷ་རི་པ། (“The Eternal Potter”)

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #63

Kumbharipa was a potter bored into despair by the repetition and meaningless tedium of his profession of making pottery. Deeply depressed and on the verge of suicide, he met a teacher who pointed out the universal nature of his unhappiness and suffering. Pointing out the symbolic understanding of the pottery wheel being like the wheel of life, our passions and thoughts being like the clay, and 6 pots being like the 6 realms; Kumbharipa practiced this insight and became enlightened entering a Lao Tzu type wu wei state with the “potter’s wheel spinning by itself and pots spring from is a joy sprang from this potter’s heart.” Mahasiddha #63

Lakshmincara ལཀྵྨཱིངྐ་རཱ།། (“The Princess of Crazy wisdom”)

c. 8th Century CE

Born into a royal family and pledged as a wife to the king of Ceylon, when Lakshmincara saw the king for the first time hunting and killing animals, she gave away her large dowry to the common people, pretended madness to stop the wedding, and moved to the charnal grounds to practice and realize enlightenment. She survived on food thrown out for dogs and took an untouchable latrine cleaner as attendant and first student. She became famous with many disciples. Her former fiancé’s father, the king Jalendra also wanted to become a disciple but she instead referred him to her student, the latrine sweeper who became his teacher. Mahasiddha #82

Layman Pang 龐居士

740 – 808 CE

Layman Pang 龐居士 Páng Jūshì, Hōkoji (740–808)

Successful merchant, family man, celebrated lay Buddhist; like Vimalakīrti and Marpa the translator, Pang exemplifies possibilities of the highest realization and enlightenment for people in everyday walks of life without needing to live in a monastery or remote cave, without being a yogi, monk, or nun. He did however worry about his success and wealth becoming an impediment to his spiritual path and at one point loaded all his riches in a boat that he sunk in a river. He and his family then traveled around China visiting great teachers and surviving by making and selling bamboo utensils. These travels and his words were immortalized in Blue Cliff Record koans as was his daughter Ling Zhao’s words, "Neither difficult nor easy, on the hundred grass tips, the great Masters' meaning" and "Not difficult, not easy—eating when hungry, sleeping when tired."

Li Bai 李白 (Li Bo)

701 – 762 CE

The greatest Chinese poet so widely respected that a crater on the planet Mercury was named after him, that he would appear as a character in books written by Hermann Hesse, John Steinbeck, Guy Gabriel Kay, Simon Elegant, Ursula Le Guin, and Philip K. Dick.. Immensely influential during his own time as well as subsequent generations in China, his influence extends to American Imagist and Modernist poetry through poets like Ezra Pound, Charles Bukowski, and Derek Walcott. Mastering Confucius at 10, he began writing poetry still famous today. At 12 he went to live in the mountains studying and writing, returned and wandered, married but but didn't make enough money so his wife left with their children. He became a favorite of the emperor, was rejected, wandered again, was imprisoned, sentenced to death, released to wander again, and legended to drunkenly die in a river while trying to embrace the moon's reflection.

Lilapa སྒེག་པ། (“Master of Play”)

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #2

“He Who Loved the Dance of Life,” Lilapa was a king who wanted to become enlightened but didn’t want to leave the luxury and privilege of his kingdom. A wandering yogin gave him practices he could do surrounded by his riches, power, musicians, and wives. He devotedly practiced, attained realization, and became famous for his philanthropy and kind goodness. Like Epicurus in the West, Lilapa taught and exemplified how spiritual realization doesn’t depend on asceticism, rigid discipline, and self-denial but harmonizes more with appreciation, cheerfulness and respect.

Lin Mo Niang 林默娘

970 CE –

Lin Mo Niang (silent girl) 林默娘 akaMa Zhou, Mazu, Matsu, Tian Hou (c. 970)

"Empress of Heaven,”patron of seafarers, Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist adept, rainmaker, and Fujianese shamaness from an impoverished and uneducated fishing village where no one could read; Lin Mo Niang lived during a time of mass migrations from China’s north when refugees blended their culture with her local one. Most popular today in Taiwan but banned in Mainland China, her following called Mazuism has over 1500 temples in 26 countries, and statures as high as 139’ (42.3 meters). Equated with Guan

Liú Yǔxī 刘禹锡

772 – 842 CE

"Mad old man poet," politician, and philosopher

Poet, philosopher, writer; Liu Yuxi grew up in the political chaos of the time and transitioned from tutor to an heir apparent, secretary to a military governor, a high political post of Investigating Censor, to friend of many literary giants of the Tang Dynasty. He was banished, recalled, banished again because of a satirical poem, then made a provincial governor, and later governor of Suzhou. Along with famous poet/governor Bai Juyi he was known as one of the “two mad old men.” His poetry became some of the most famous throughout China, the other East Asian countries, and now—through insightful translations like Red Pine’s—in the West as well.

Lü Dongbin 呂洞賓 (Lü Tung-Pin)

796 CE -

Scholar and poet, de facto leader of the 8 Immortals, founder of the School of the Golden Elixir of Life and the internal alchemy tradition; Lu Dongbin is named in famous Chinese proverbs and wrote the Secret of the Golden Flower. An easy-to-anger, prolific poet and ladies man prone to bouts of drunkenness; he’s considered an emanation of the Bodhisattva Guanyin (Avalokiteśvara) dedicated to helping people realize wisdom and learn the Tao. Continually popular in folklore, he was portrayed by Jackie Chan in the movie The Forbidden Kingdom.

Lu Huiqing

1031 – 1111 CE

Ally to Wang An-shih and aid to his political reform, Lu Huiqing’s commentaries demonstrate his deep Taoist understanding and ability to apply Lao Tzu’s insights and suggestions to his contemporary political and social situation. A seminal resource for Chiao Hung, the Emperor Shenzong of Song requested and received these commentaries in 1078 and used them to strategize and implement radical new policies to improve the situation for peasants and the unemployed. These reforms foreshadowed and helped inspire the modern welfare state.

Lūipa ལཱུ་ཨི་པ། (“The Fish-Gut Eater” )

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #1

In the noble but uncommon tradition of the 1% voluntarily equalizing wealth, Luipa disdained his excessive riches and though born a king, like the Buddha he left his kingdom for a spiritual path. More than just his wealth though, Luipa’s teacher gave him a practice of abandoning his royal blood/Brahmin, food-purity culture prejudice by for 12 years eating only the fish guts normally intended only for dogs. This made him an untouchable and closed the door back to his former status and privilege. As a mendicant sage, he became an important teacher to many and passed into legend.

Machig Labdrön མ་གཅིག་ལབ་སྒྲོན།

1055 – 1149 CE

Nun, mother, wandering yogini, mind Stream emanation (tulku) of Yeshe Tsogyal that later became Jetsun Rinpoche; Machig Labdrön came from a Bön family and blended these shamanistic teachings with Buddhist Dzongchen to develop several Tibetan Vajrayana lineages as well as Mahamudra Chöd—a Prajñāpāramitā practice of “Cutting-Through-the-Ego” and experiencing emptiness. A child protege and scholar at a very early age, she left a comfortable and honored place in a monastery to wander and live with beggars and sleep wherever she found herself. Though criticized for having children, her teaching became so popular they spread from Tibet to India. In Tibet, it’s said she overcame the patriarchal bias of her times and gave teachings to as many as 500,000. Her lineage continues the Mahasiddha tradition of India and the Crazy Wisdom teachings of Tibet.

Manibhadra

10th C. CE

One of the 84 Mahasiddhas in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and described as the “Happy Housewife’ siddha” and “Model Wife,” Manibhadra as a teenager met her teacher Kukkuripa and bravely followed him into the cremation grounds where she began practicing Vajrayana. Instead of leaving the conventional world to practice though, she married, had children and brought her spiritual practice into her daily life demonstrating the sacredness and enlightenment in the simple, ordinary world and becoming an exemplar to householders.

Marpa Lotsawa

1012 – 1097 CE

Founder of the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, teacher to the great Milarepa, businessman, farmer, family man and exemplar of enlightenment in everyday life; Marpa made many, perilous journeys to India and Nepal where he studied Vajrayana teachings, translating and bringing them back to Tibet. Wild, uncompromising, and outrageous; he flourished on physical dangers, psychological and spiritual challenge bringing “tasting the flavor of realization” into his translations that went to the depth of understanding rather than staying on the surface of the words.

Medhini མེ་དྷི་ནཱི། (The Tired Farmer)

8th century CE

Mahasiddha #50

A low-born farmer working from early morning until late at night, Medhini decided to embark on a spiritual path but couldn’t get thoughts about farming out of his mind. His guru taught him how his thoughts about cultivating the earth could be understood, practiced, and applied to the cultivating of his own awareness. Having realized the non-duality of farming and realization, he discovered the unconditioned nature of reality and went on to teach and benefit countless students.

Mekhala མེ་ཁ་ལཱ། (“The Elder Severed-Headed Sister” )

late 9th century

Mahasiddha #66

One of two unmarried, mischievous daughters; Mekhal’s father married her off to an unsuspecting boy from another village. He soon realized though and an intense and constant “battle of the sexes” began. As their lives sunk into more and more misery, the younger sister—Kanakhala—suggested running away to another country. Mekhala, however, realized that their problems were self-created and would follow them wherever they travelled. This realization somehow seems to have triggered an encounter with a famous guru who initiated them onto a spiritual path. After 12 years, they returned to the guru but brought no offerings. According to the story, the guru asked for their heads and they immediately cut them off with “the keen-edged sword of pure awareness.”

Mekopa མེ་ཀོ་པ། ("Guru Dread-Stare")

1050 CE –

Mahasiddha #43

Mekopa, མེ་ཀོ་པ། Guru Dread-Stare (11th century)

Always cheerful and kind Bengali food merchant taken as a student by a yogin customer, Mekopa saw into the vastness of his own mind, the uselessness of chasing desires, and harmfulness of action based on duality. His realization led him far beyond the limits of status quo, conventional social standards and behavior; into a lifestyle unbound by concern for people’s opinion, wandering about a cremation ground “like a wild animal” and into towns like a mad saint with dreadful, staring eyes. Mahasiddha #43

Milarepa རྗེ་བཙུན་མི་ལ་རས་པ།

1052 – 1135 CE

Black magician enemy-killing sorcerer transformed into a great Tibetan folk hero, poet, singer-songwriter and saint; Milarepa always refuted any hero worship or deification stressing his humble background and realization that anyone could achieve. Overcoming powerful, psychological demons, he left far behind fame, fortune, pleasure, power, even companionship and after many years of solitary meditation wandered throughout Tibet teaching and leading students to illuminating, egoless, complete sanity beyond the corruptions of a belief in a separate self. Profound without pretense, ageless because authentic, livable because so simple; Milarepa’s teaching and inspiration continues.

Minapa མཱི་ན་པ། (Macchaendra, Matsyendra, "The Hindu Jonah")

10th Century CE

Mahasiddha #8

Bengali fisherman, “India’s Jonah,” a hunter who became the hunted and swallowed by his prey; Minapa unexpectedly and unintentionally heard some highly secret dharma teachings, practiced alone for 12 years and then became a famous mahasiddha and teacher. Protector deity of Nepal, bringer of rain in drought, and original science of yoga teacher; Minapa is also revered in Nepal as the bringer of the first rice seeds. A symbol for the wisdom born in solitude and the journey into deep subconscious depths, he’s know for saying, “What a precious jewel is one’s own mind.”

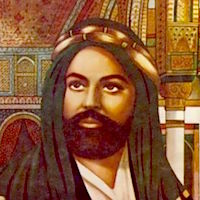

Muhammad محمد; محمد;

570 – 632 CE

Gfted political leader, sage lawmaker, just judge, sincere devotee of integrity; Muhammad was praised by Leibniz, Rousseau, Napoleon, and Thomas Carlyle but Voltaire thought of him as a symbol of fanaticism and called him "a sublime and hearty charlatan.” Although his integrity can be argued, his influence is indisputable. Founder and prophet of Islam, he launched a political and religious revolution that rapidly transformed a poverty-drenched Arabia from a desert of motley, contentious tribes into a force that within 100 years conquered half the Mediterranean world, Byzantine Asia, all of Persia and Egypt, and most of North Africa. A simple ascetic in most ways, he used eye shadow and perfume, dyed his hair, and kept an active harem. Building on the Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian traditions; he described elaborate visions of both heaven and hell that forged a unified, monotheistic tradition that unified the Arabs, spread throughout the world, and is still a potent influence today.

Nansen, Nanquan Puyuan 南泉普願

749 – 835 CE

Nansen, Nanquan Puyuan 南泉普願 Nánquán Pǔyuàn (749 – 835)

Tang Dynasty Chán master and inspiration for the “Golden Age of Chan;” Nansen, after 30 years meditating in a mountain retreat, came back to the world of people becoming a famous teacher and a key figure in many illuminating Zen anecdotes. Renowned for untangling the deep truth caught and hidden in the net of words, his direct communication and activity with students (including Joshu, Zhàozhōu Cōngshěn) directly provoked many enlightenment experiences. His koans appear in The Gateless Gate, The Blue Cliff Record, and The Book of Serenity.

Nāropā

955 – 1040 CE

Born a high status Bengali Brahmin, Nāropā became a great debater, scholar, Nalanda abbot, and “Guardian of the Northern gate.” In a famous encounter with his teacher, Tilopa, he realized that he only understood the words of the teachings, not the true sense and began a journey that defines the criteria for lineage holders on this list. An important teacher to many enlightened teachers and mahasiddhas including Atisa, Maitripa, Dombipa, Marpa and many other Tibetans who took these teachings to Tibet where they flourished as they were destroyed in India by an Islamic invasion said to have killed over 400 million people.

Niguma

11th C. CE

“Dakini of timeless awareness,” co-founder of the “secret lineage,” the Shangpa Kagyu school of Vajrayana Buddhism, wife and later disciple of mahasiddha Naropa, teacher to Marpa the translator; Niguma wrote 13 books basic to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and had a deep and continuing influence on the foundations and practices of Buddhism in Tibet and other countries. One of the most important and influential teachers of her time, she established a complete set of spiritual practices called the Six Yogas of Niguma that is still practiced, studied and greatly appreciated today.

Nirgunapa ནིརྒུ་ཎ་པ།

(9th century)

"The Enlightened Moron" #57

Born into a low-caste family and inflicted with a moronic lassitude, depression, and such a lack of intelligence and skill that his parents thought it would have been better had he not been born; Nirgunapa sunk into the depths of suffering and despair. While unable to spark even enough motivation to beg for food, a teacher found him in a remote place and gave him enough food to survive. The teacher offered to give him a spiritual practice and Nirgunapa accepted with the condition that he not have to get up off his back. Exemplifying the principle of basic goodness in spite of possessing none of the materialistic qualities valued by society, he became a great teacher. While wandering through villages, when he met someone who asked him a question, he answered only by gazing into their eyes and crying which awoke in them a deep sense of compassion.

Omar Khayyám

1048 – 1131 CE

Persian Astronomer-Poet, prophet of the here and now

In the west most famous for his poems but Omar Khayyam was also a political advisor, “philosopher of the world,” one of the most influential scientists of his era, “one of the greatest mathematicians of medieval times,” and “without equal in astronomy and philosophy.” A prophet of the here and now, mystical Sufi teacher and free-thinker who rejected theology; he reformed the Persian calendar to a form more accurate than our own today, wrote the most important until modern times book on algebra as well as many others on astronomy, geography, and mechanics. His poems—known as the Rubáiyát—not only rejected Islamic belief and Christian morality, but the nature of religion itself.

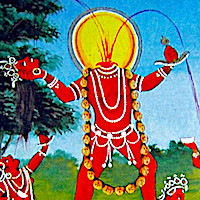

Padmasambhava པདྨཱ་ཀ་ར། ("The Lotus-Born", Guru Rinpoche)

8th century CE

Known as “The Second Buddha” and founder of Tibetan Buddhism the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet, and the Nyingma school; Padmasambhava came to Tibet at the request of King Trisong Detsen. Venerated also in northern India, Bhutan, and Nepal; Padmasambhava became famous for subduing “demonic forces” that prevented Buddhist teaching from becoming rooted in Tibet. Rather than conquering these negative influences, he took the tantric approach of transforming the demons into protectors. His name and symbolism comprise one of the most common and popular mantra-prayers in Tibetan Buddhism and is believed to communicate and inspire sacred teachings of transformation.

Peter Abelard Pierre Abélard

1079 – 1142 CE

Peter Abelard, Pierre Abélard (1079 – 1142)

Described as "the keenest thinker and boldest theologian of the 12th Century,” Abelard was on a strong path to becoming a pope when he fell in love with Héloïse and instead wrote some of the most important books of his era while becoming a legend in the history of romantic love, of inner certainty over external, status quo coersion. In his early life, thousands of students coming from many countries came to hear him teach. His fame and admiration immense, but his love of Héloïse led to his castration by her uncle, his becoming a monk, and her becoming a nun. This challenged the physical side of their relationship but their deep emotional bond continued through letters written the rest of their lives.

Prince Shotoku

574 – 622 CE

The son of emperor Yomei, Shotoku inspired a devotional tradition of protecting Japan, the Imperial Family, and Buddhism. His commentary on three famous Buddhist sutras in 615 CE are considered the first Japanese text. He also wrote the first Japanese constitution and is credited with creating a strong and united Japan. Still revered, his picture is on the Japanese 10,000 yen currency note.

Rabia Basri رابعة العدوية القيسية (Rābi‘a al-‘Adawīyya)

714 – 801 CE

Muslim mystic, “queen of saintly women,” and most important early Sufi poet; Rabia Basri rose from the poverty and slavery of her youth to become the most famous and influential Sufi woman of Islamic history known as “the queen of saintly women.” She had many disciples and became an important influence on the leaders of her time as well as an early voice against spiritual materialism and Islamic patriarchy. She taught a doctrin of Divine Love known as Ishq-e-Haqeeqi that is still practiced today and emphasized spiritual practice without desire for reward or fear of punishment.

Rinzai Gigen 臨済義玄 (Línjì Yìxuán)

? - 866 CE

Student of Huangbo Xiyun, iconoclastic founder of a major Chán Buddhist school and one of the Five Houses of Zen, Rinzai; Gigen or Linji fiercely challenged students who accepted the superficial, conceptual meaning of buddhist teachings rather than penetrating the true meaning deeper than the words to find genuine wisdom and understanding. A book of his sayings recorded by one of his students, The Record of Rinzai (Zen Teachings of Rinzai), became one of the main texts for the Rinzai school as well as a big influence on buddhism and the evolution of consciousness in general. Known for his uncompromising approach to teaching that included yelling at and hitting his students, he directly continued the Buddha’s flower-sermon styleof non-conceptual teaching.

Saraha

8th century CE

Earliest Mahasiddha, founding father of the Buddhist Vajrayana and Mahamudra tradition; Saraha was expelled from a monastery for drinking alcohol, found a young low caste bride, became a maker of arrows, and went on to write the main Mahamudra meditation text and become a great yogi and master song writer. Like Lao Tzu, he followed the same “Inborn Natural Way” and began the lineage which descended through time to Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa, Milareapa and now to the Gyalwang Karmapa.

Sarvabhaksha སརྦ་བྷཀྵ། ( “The Glutton” )

late 8th, early 9th century

Mahasiddha #75

A born hungry, low caste man with an enormous appetite, Sarvabhaksha constantly dreamed about food, even after a huge feast. A chance meeting with the great siddha Saraha led to a vision of hungry ghosts—wretched wraiths with mouths like the eye of a needle and stomachs like an empty mountain—and a spiritual practice based on generosity and compassion. His insatiable desires shifted from food for himself to happiness for all sentient beings and he became a great teacher himself. His story demonstrates the the reality-changing power of visualization, both for the positive and the negative—on one hand the capacity of a Hitler to create a black magic hallucination creating the holocaust; on the other, positive visions like the American Dream, the Christian “Heaven on Earth”, and the Eastern Shambhala myths.

Śavaripa ཥ་ཝ་རི་པ། (Śabara, “The Hunter”)

8th – 9th C. CE

Mahasiddha #5

From the lowest wrung of untouchables and a wild, aboriginal tribe, the Śabaras; Shavaripa became a forefather of the Tibetan Kagyu lineage and a famous teacher. From a tradition known for crazed sexual passion, smoking marijuana, and drinking alcohol from a skull cup; he and his wife transformed their tradition into a potent symbol for tantric Buddhist practice. From a skilled and proud hunter, Shavaripa became a beacon of vegetarianism. Known as “Saraha the Younger” and a student of Nagarjuna, he transmuted aggression into loving kindness for all beings and through his disciple Maitipa transmitted this tradition to Marpa who brought it to Tibet.

Shantideva ཞི་བ་ལྷ།།། (Bhusuku, Śāntideva)

685 – 763 CE

Son of a king, Indian scientist, Buddhist monk, "The Great Poet," and unliked Nalanda University scholar known for not studying, practicing meditation or showing up for events; Shantideva was challenged by the university to give a talk as proof that he really belonged there but really as way of getting rid of him. Shocking the scholars and monks who wanted to expel him, he gave a talk that became the famous Bodhicaryavatara, The Way of the Bodhisattva or Entering the Path of Enlightenment. Leaving the University and following Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka philosophy, his teachings became a strong foundation for the Mahayana tradition. Mahasiddha #41

Shantipa ཤཱནྟི་པ། ("The Academic")

late 10th to mid-11th century

Mahasiddha #12

“Keeper of the Southern Gate,” student of Naropa, teacher of Atisa, and an academic famous throughout ancient India; Shantipa was invited by the king of Sri Lanka to teach his people. He visited the island with 2000 monks and big baskets of Dharma texts carried by horses and oxen. Welcomed by the people with joy, openness, and excitement, he taught the Buddhist teachings for 3 years and received immense and valuable gifts, honor and fame. Returning to India he met one of his earlier disciples, Kotalipa who had become a Mahasiddha himself. This made Shantipa realize that he was seduced the words of his own teachings and had missed the sense. He became a disciple of his disciple, began his practice again at a very old age, and eventually realized the sense beneath the words he had expounded for so many decades.

Shen Kuo 沈括 (Mengxi)

1031 – 1095 CE

Greatest scientist of his age, statesman, inventor, poet, finance minister, horticulturalist, engineer, art critic, diplomat, military general, musician, and commentator on ancient Daoist texts; Shen Kuo discovered the magnetic compass needle and the concept of true north which revolutionized navigation 400 years before known in Europe, popularized Bi Sheng’s invention of moveable type 400 years before Gutenberg, researched and described climate change, made the first raised-relief map, described UFOs and beneficial insects, re-discovered an ancient Chinese surveying tool unknown in Europe until 1321. Politically aligned to Wang Anshi, he was impeached, exiled and spent his older years with the "nine guests" — playing music, weiqi (Go), Chan meditation, painting, tea, alchemy, poetry, conversation and wine.

Shyalipa ཥྱ་ལི་པ། (Śyalipa, "The Jackal-Yogin")

1000 – 1100 CE

Mahasiddha #21

A poor laborer terrified of jackals but living on the edge of a cremation ground full of jackals, Shyalipa became so terrified he couldn’t sleep at night and only a little during the day when he dreamed about jackals. Kind to a wondering teacher who gave him a practice called “the fear that destroys fear,” he learned to meditate on the jackal howls until he could recognize the indivisibility of emptiness and sound, the complete appreciation of his self-liberated fear. Rather than running away from his terror or trying to get rid of it, he leveraged overcoming his fear of jackals to overcoming his fear of death and the suffering of life, he “destroyed his fear with fear,” and wearing a jackal skin became an important teacher himself. Mahasiddha #21

Sima Guang 司马光

1019 – 1086 CE

"Greatest of all Chinese historians”

“The greatest of all Chinese historians,” politician, scholar-official, and major cat-breeder; Sima Guang opposed Wang Anshi's reforms to help the poor against the rich but wrote a pioneering, universal history of China that influenced the world’s political evolution. Also a lexicographer, he spent decades writing his time’s most comprehensive dictionary that included 31,319 Chinese characters. His book, Family Precepts (司馬溫公家訓) became a powerful influence on both Chinese and Japanese culture. A genius with a monumental memory, Sima’s quick thinking when he was only 7 famously saved the life of his friend. He loved reading "to the point of not recognizing hunger, thirst, coldness or heat” and when involved with a complicated writing project, he slept on a wooden log so he would sleep less and be able to work more. His scholarship—far from just intellectual speculation—became a guiding force for emperors but during his life and after his death.

Solomon ibn Gabirol שלמה בן יהודה אבן גבירול (Avicebron)

1021 – 1070 CE

The greatest poet of his age, a Jew for over 600 years regarded by Moslems as a Muslim and by Christians as a Christian, believed a Christian by William of Auvergne who called him “the noblest of all philosophers;” Gabirol grew up in hardship and wandered for years in such poverty that “a fly could now bear me up with ease.” A huge influence on both Christianity and Islam, he championed reason over faith, compiled a book of proverbs independent from Judaism that included wisdom sayings from China, and wrote one of the greatest poems in all of Hebrew literature.

Songtsen Gampo སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ

569 – 649 CE

Founder of the Tibetan nation, Songtsen Gampo unified Tibet, introduced Buddhism, many new cultural and technological improvements, created the Tibetan alphabet, the first constitution and model laws. After winning a war against China and influence over Nepal, he was given Nepalese and Chinese princess wives who helped him establish trade with surrounding countries and a golden age for Tibet. In Tibetan tradition, both wives are considered incarnations of Tara, the Goddess of Compassion, and Songtsen Gampo as a manifestation of the bodhisattva, Avalokiteśvara.

Su Che 呂洞 (Su Zhe)

1039 – 1112 CE

Great writer of the Tang and Sung dynasties

Famous politician and essayist, one of "The Eight Great Men of Letters of the Tang and Song Dynasties,” exiled for his political criticisms; Su Zhe skillfully criticized social conditions in an effort to influence the emperor into creating better living situations for the common person. Champion of reforms to help the poor and protect them from the rich and powerful and also to help the rich realize that their hoarding and selfishness only made them more vulnerable to revolt, robbery, and revolution. The temple where he lived and taught is now a museum and one of China’s more famous cultural attractions.

Su Shi 苏轼 (Dongpo, Su Tungpo)

1037 – 1101 CE

"pre-eminent personality of 11th century China"

Writer, statesman, poet, painter, calligrapher, pharmacologist, and important political figure; Su Shi wrote some of his time's most well-known poems and prose as well as essays on topics from travel to the iron industry. An exceptional and highly honored scholar, while serving in the Hangzhou government, he constructed the famous pedestrian causeway across West Lake. His poems got him into political trouble leading to two long exiles and imprisonment; but also, they brought him a fame that spread to many other countries and continues today. His poems on Buddhist topics became an important influence on Dōgen, founder of the Zen Sōtō school.

Taizong of Tang 唐太宗 唐太宗 (Li Shimin)

598 – 649 CE