Tao Te Ching

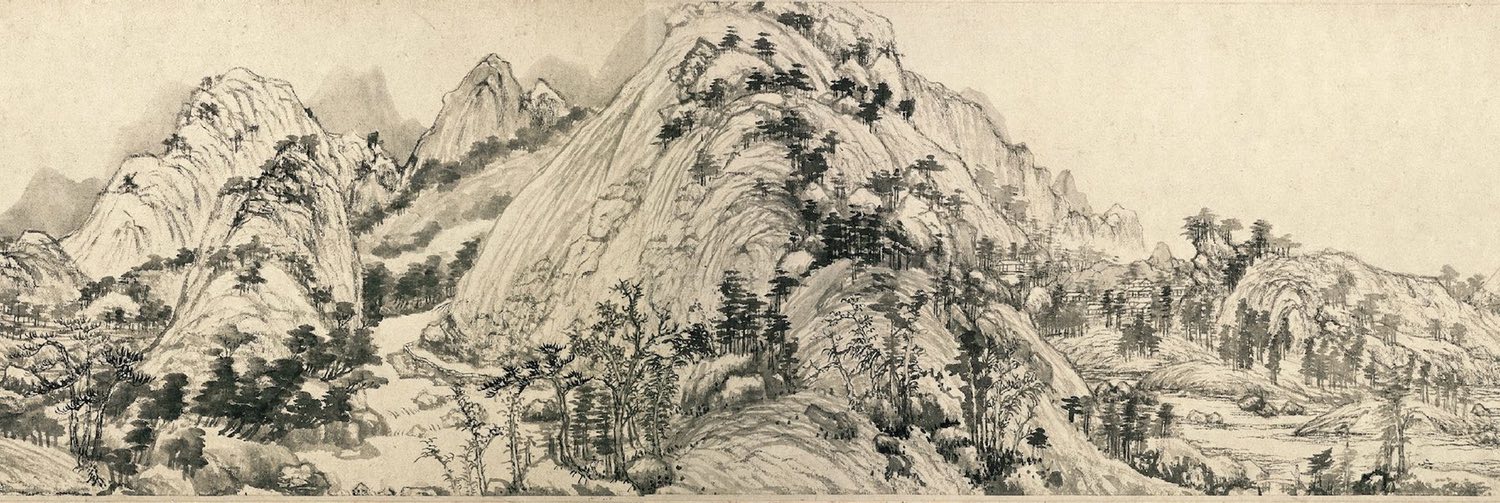

Dunhuang cave painting, mid-10th century

5 Dynasties 10 Kingdoms (907 – 960 CE)

The golden age of the Tang Dynasty deteriorated into weakness and corruption as concubine-infatuated emperors neglected the state, self-serving officials thought only about themselves, politicians launched rebellions, peasants revolted, and surrounding tribes attacked and broke the empire into many parts. This led to periods called the 5 Dynasties 10 Kingdoms, later the 5 Kingdom of Dali. These governments were as weak and ineffective as they were short plunging China into a period of chaos and civil disorder. The last long period of a multi-divided Chinese history, this period set the distinct regional Chinese identities still defined today. It transitioned the Tang internationalism into the Song Dynasty national culture, increased economic growth, and birthed innovations in ceramics, painting, and Taoist-inspired art that emphasized the sacredness of nature.

Sages (21)

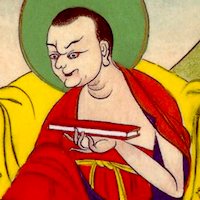

Aciṅta ཨ་ཙིངྟ་།། ("The Avaricious Hermit")

862 – 912 CE

Mahasiddha #38

Acinta ཨ་ཙིངྟ་། Achingta, “The Greedy Hermit” (second half of 9th century)

Born into extreme poverty, constantly and completely fixated on becoming wealthy; Acinta couldn’t forget his intense desire for riches. Tormented by his greed and unable to escape from it, he met a teacher who gave him a Jambhala wealth practice and initiation into the irresistibleness of a thought-stopping empty mind free from gaining ideas. His dreams of wealth dissolved into a realization of nothing to gain, he became known as “The Thought-Free Guru,” served countless beings, and initiated many disciples into this ultimate reality. Mahasiddha #38

Bhikṣanapa བྷི་ཀྵ་ན་པ། ("Siddha Two-Teeth")

940 CE –

Mahasiddha #61

Bhikshanapa བྷི་ཀྵ་ན་པ། “Siddha Two-Teeth” (10th century CE)

Low caste and very poor, Bhikshanapa unexpectedly inherited some wealth. Like most people today winning a lottery or inheriting unaccustomed riches, he quickly lost it all along with his fair-weather friends. This led to a period of intense self-loathing and depression but also an openness to meeting and hearing a teacher and new way of experiencing the world. Seeing through his consumerism andspiritual materialism, he metaphorically (and possibly physically too), lost all but two of his teeth which became symbols for the balance and harmony of wisdom and skillful means. Resuming his external life style of roaming from village to village, he transformed from a miserable, needy beggar only thinking about himself into a wonderful teacher constantly dedicated to helping others. Mahasiddha #61

Campaka ཙ་མྤ་ཀ (“The Flower King”)

820 CE –

Mahasiddha #60

Extremely wealthy, powerful, caught up in pleasure, and sitting on a throne made from sweet-smelling flowers; Kampala met a wandering yogi. He tried to impress the sage with the splendors of his kingdom and the beauty of his flowers but the sage told him the truth, that his flowers smelled great but his body not so much, that his realm was wonderful but before long it and he would be gone. Realizing the superficiality and meaninglessness of his life, Kampala began a spiritual path but only shifted his physical materialism into spiritual materialism. Directed to focus his meditation on “the flower of pure reality,” he practiced and finally realized the empty essence of his mind. Mahasiddha #60

Cauraṅgipa ཙཽ་རངྒི་པ། ("The Dismembered Stepson")

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #10

Saintly son of a king, Cauraṅgipa’s arms and legs were cut off when he refused the amorous advances of his step-mother who lied and slandered him. The servants offered to take the body parts from their own children but he refused, not wanting to cause harm to others. Left to die under a tree, he met his guru Minapa who gave him meditation practices that saved his life and led to his complete realization, “the one taste of all things.” His physical loss of limbs became a foundation and benefit to his practice. (graphic credit: Robert Beer) #10

Chamaripa ཙཱ་མཱ་རི་པ། (Cāmāripa, “The Siddha Cobbler”)

840 – 940 CE

Mahasiddha #14

A poor cobbler in ancient India, Chamaripa worked long hours making and repairing shoes while he dreamed of a higher, more meaningful life. Disgusted with the emptiness of his life he begged teaching from a wandering teacher and began a practice of visualizing his work as meditation practice, his tools and materials as symbols for deep understandings. He discovered how the thread that tied his shoes together was like the thread of emptiness (shunyata) that connects a core enlightenment back through our graspings for fame, fortune, pleasure, and power. Mahasiddha #14

Ḍeṅgipa ཌེངྒི་པ། (“The Courtesan's Brahmin Slave”)

9th Century CE

Mahasiddha #31

Brahmin minister to a king who left his wealth and status for a spiritual path, Ḍeṅgipa met his guru but because he had no appropriate gift to give offered his body as a slave. His guru then - to reduce his royal pride, racial discrimination, and to give him a practice - sold him as a slave to a prostitute. After 12 years of service mainly threshing rice, he discovered the one taste of all things, merged space and awareness, and became spiritual teacher to the prostitute as well as to the hundreds of people in that district. Mahasiddha #31

Dharima

10th century CE

Prostitute, consort of the famous Mahasiddha Tilopa, slave owner and student of Mahasiddha Luipa (probably a different person with same name and profession); Dharima and Tilopa started on this spiritual path together, practiced together for many years, and when enlightened taught together. They learned the "Illusory-body" yoga from Nagarjuna’s tradition, Dream yoga from Caryapa, Cakrasamvara and the Clear Light from Lavapa, and from the woman saint Subhagini, Candalini-yoga and the Hevajra tantra. They forged these 4 traditions into what became the Kagyu lineage of Mahamudra that continues powerfully today through teachers like Chogyam Trungpa and the Karmapas.

Dharmapa thos pa’i shes rab bya ba

915

“The Perpetual Student” — Mahasiddha #36

Dharmapa lived his life as a scholar, a professor, a pandita. He spent his entire life studying and teaching but gave little time or attention to meditation or other practices. He didn't become aware of the gap this left in his awareness until he was old and blind. He realized his need for a teacher but was no longer in a position to fine one. A dakini appeared in a dream however, and taught him the difference between analytical understanding and realization. He showed Dharmapa how he could—like a blacksmith melting pieces of iron into a single ingot—melt all the disparate strands of his knowledge into a unified experience of true mind and wisdom.

Dhilipa དྷི་ལི་པ། (“The Epicurean Merchant”)

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #62

Dhilipa had a sesame oil pressing business that did really well and made huge profits. He devoted this wealth to personal pleasure-seeking and is said to have had at each meal 84 main courses, 12 deserts, and 5 kinds of beverages prepared by the best chefs of the time. After one of these sumptuous banquets, a dharma teacher guest questioned him about how far his pleasure seeking was really taking him and pointed out that he could go on making more and more money but it wouldn’t bring him any more true happiness or realization. Like he extracted oil from sesame seeds, Dhilipa then extracted dualistic concepts from experience, realized the union of opposites, and burned the pure flame of awareness. Mahasiddha #62

Dombipa

10th C. CE

Enlightened ruler of Magadha (Kashmir), Dombipa treated all his subjects like a “father would treat his only child” but his country suffered almost endless war, crime, famine, and poverty. He brought back prosperity, peace, and health but when he took a low caste “untouchable” as consort and started drinking large amounts of alcohol, the shocked people forced his abdication. After 12 years when the country’s problems returned, they begged him to return which he did “riding on a pregnant tiger” with his consort. To rule them again, he asked that they abandon the caste system. When they refused he went back into his meditation saying, “My only kingdom is the kingdom of truth.” This lineage continues with the Trungpa Tulkus.

Ferdowsi فردوسی (Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi)

940 – 1020 CE

"undisputed giant of Persian literature"

Philosopher, poet, and one of the world's most influential literary figures; Ferdowsi wrote what became Iran's national epic as well as history's longest poem written by a single poet. Considered the "father of the modern Persian language," he influenced all the writers who followed him, regenerated the Persian language, and revived many cultural traditions.

Goraksa ཤྲཱི་གོ་རཀྵ་ནཱཐ྄། (Nāth Siddha Gorakṣa, "The Immortal Cowherd")

10th Century CE

First haha yoga teacher, founder of India’s largest yoga sect, and non-sectarian Tantric leader; Goraksa assimilated Buddhist insight and understanding into a Hindu context free of duality and integrated tantric practices into Buddhist philosophy. His life symbolizes and his teachings reinforce that every condition and situation people find themselves in has equal potential for realizing the highest awareness. He emphasized the potential in even the most negative circumstances and taught to appreciate everything rather than fighting against our experience and trying to attain a fantasy of what we might think is better.

Indrabhūti ཨིནྡྲ་བྷཱུ་ཏི། ("The Enlightened Siddha-King")

892 CE –

Mahasiddha #42

Indrabhuti ཨིནྡྲ་བྷཱུ་ཏི། The Enlightened Siddha-King (late 9th century)

“The first tantrika,” archetypal tantric king, and inspiration for several tantric lineages; Indrabhuti for political reasons pledged his Buddhist sister Laksminkara in marriage to the prince of a neighboring Hindu kingdom. She went to live with the neighboring prince but soon became disillusioned with the materialism, superstition, and decadence of her new country. Late one night she fled the palace and found a cave in the mountains where she lived and practiced meditation, attained enlightenment and scandalously started teaching untouchables. This greatly upset the Hindu king but inspired Indrabhuti to do the same and leave the comfort of palace life to devote himself completely to his spiritual path. He rejected however a path that rejected sensual pleasure and sex and practiced the Guhyasamaja father-tantra in the Anuyoga Dzogchen lineage. Mahasiddha #42

Jālandhara ཛཱ་ལནྡྷ་ར་པ། ("The Ḍākinī's Chosen One")

888 CE –

Mahasiddha #46

Jalandhara ཛཱ་ལནྡྷ་ར་པ། “The Ḍākinī's Chosen One” (late 9th century)

Another wealthy and privileged brahmin who saw through the materialistic values of his culture and renounced it to search for a more meaningful life, Jalandhara left everything to live in a cremation ground meditating. Going on to become an important mother-tantra siddha, one of the nine naths, and guru to 10 of the 84 Mahasiddhas; he founded one of the two main nath lineages (A Hindu tradition favored by Kabir that blended Shaivism, Buddhism and Yoga traditions using Hatha Yoga to transform the physical into awakened perception of “absolute reality”), taught practices that unify the male and female forces, dissolve the subject/object dichotomy, and open the non-dual doors of perception. Mahasiddha #46

Khaḍgapa ཁཌྒ་པ། ("The Fearless Thief")

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #15

Hiding in a cremation ground after a failed robbery, Khadgapa met Carpati, an enlightened yogi and asked for some meditation practices that would make him into an invincible, uncatchable thief. Carpati gave him practices and instructions for finding the “radiant sword of undying awareness.” Khadgapa thought this sword would cut his physical enemies but instead it cut through his real foes: anger, hatred, aversion, desire, greed, sloth and stupidity. In spite of his life of crime, Khadgapa became a great Mahasiddha himself proving that any lifestyle and profession can launch the highest realizations. #15

Kukkuripa ཀུ་ཀྐུ་རི་པ། ("The Dog Lover")

915 CE –

Mahasiddha #34

Kukkuripa “The Dog King” ཀུ་ཀྐུ་རི་པ། (10th century CE)

A wandering ascetic, Kukkuripa found and adopted a starving dog brought it back with him to the cave where he lived and meditated. Kukkuripa’s meditation practice took him to pleasurable, psychological god realms but memories of his dog connected him back to the real world where he saw his loyal dog sad, thin, and starving. Spurning the luxury, comfort and extravagance; he returned to the cold, dark, very uncomfortable cave out of compassion for the dog. The dog then became his teacher blending his mind-stream with the deepest insight of all the Buddhas. Naropa sent Marpa to study with him and he became one of Marpa’s most important teachers, famous for his songs of realization, and a “patron saint” for all the downtrodden and oppressed. Mahasiddha #34

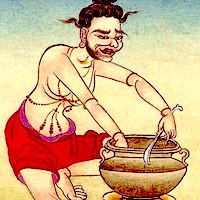

Kumbharipa ཀུམྦྷ་རི་པ། (“The Eternal Potter”)

10th century CE

Mahasiddha #63

Kumbharipa was a potter bored into despair by the repetition and meaningless tedium of his profession of making pottery. Deeply depressed and on the verge of suicide, he met a teacher who pointed out the universal nature of his unhappiness and suffering. Pointing out the symbolic understanding of the pottery wheel being like the wheel of life, our passions and thoughts being like the clay, and 6 pots being like the 6 realms; Kumbharipa practiced this insight and became enlightened entering a Lao Tzu type wu wei state with the “potter’s wheel spinning by itself and pots spring from is a joy sprang from this potter’s heart.” Mahasiddha #63

Manibhadra

10th C. CE

One of the 84 Mahasiddhas in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition and described as the “Happy Housewife’ siddha” and “Model Wife,” Manibhadra as a teenager met her teacher Kukkuripa and bravely followed him into the cremation grounds where she began practicing Vajrayana. Instead of leaving the conventional world to practice though, she married, had children and brought her spiritual practice into her daily life demonstrating the sacredness and enlightenment in the simple, ordinary world and becoming an exemplar to householders.

Minapa མཱི་ན་པ། (Macchaendra, Matsyendra, "The Hindu Jonah")

10th Century CE

Mahasiddha #8

Bengali fisherman, “India’s Jonah,” a hunter who became the hunted and swallowed by his prey; Minapa unexpectedly and unintentionally heard some highly secret dharma teachings, practiced alone for 12 years and then became a famous mahasiddha and teacher. Protector deity of Nepal, bringer of rain in drought, and original science of yoga teacher; Minapa is also revered in Nepal as the bringer of the first rice seeds. A symbol for the wisdom born in solitude and the journey into deep subconscious depths, he’s know for saying, “What a precious jewel is one’s own mind.”

Nāropā

955 – 1040 CE

Born a high status Bengali Brahmin, Nāropā became a great debater, scholar, Nalanda abbot, and “Guardian of the Northern gate.” In a famous encounter with his teacher, Tilopa, he realized that he only understood the words of the teachings, not the true sense and began a journey that defines the criteria for lineage holders on this list. An important teacher to many enlightened teachers and mahasiddhas including Atisa, Maitripa, Dombipa, Marpa and many other Tibetans who took these teachings to Tibet where they flourished as they were destroyed in India by an Islamic invasion said to have killed over 400 million people.

Yunmen Wenyan 雲門文偃 (Ummon Daishi, Yúnmén Wényǎn)

862 – 949 CE

The most eloquent Chan master

One of the most famous Zen masters in later day Japan, Ummon founded one of the five major Chán schools in China. This school compiled and wrote the Blue Cliff Record, flourished for hundreds of years, and continues today. Supported by the region's king, and famous throughout China and Korea, Ummon rejected the fame and many offered honors while building a new monastery in a more remote location. Many of his recorded statements later became koans—5 listed in The Gateless Gate, 8 in the Book of Equanimity, and 18 in the Blue Cliff Record.

Chinese Eras

Xia Dynasty 夏 (2100 – 1600 BCE)

Shang Dynasty 殷代 (1600 – 1046 BCE)

Western Zhou 西周 (1046 – 771 BCE)

Eastern Zhou 東周 (770 – 256 BCE)

Spring and Autumn period 春秋时代 (770 – 476 BCE)

Warring States period 春秋时代 (476 – 221 BCE)

Qin Dynasty 秦朝 (221 – 206 BCE)

Three Kingdoms 三國時代 (220 – 280 CE)

Southern and Northern 南北朝 (420 – 589 CE)

Tang Dynasty 唐朝 (618 – 907 CE)

5 Dynasties 10 Kingdoms (907 – 960 CE)

5 Kingdom of Dali 大理国 (937 – 1253 CE)

Western Xia 西夏 (1038 – 1227 CE)

Southern Song (1127 – 1279 CE)

Comments (0)